Anna (Joanne Froggatt) goes to buy an ice, with John Bates (Brendan Coyle) looking on

The canonical song sung near the end of season 2

Dear friends and readers,

For a third time I’m gathering in one place a handy list of the blog reviews I’ve done for a season of Downton Abbey. Here is the previous one where I gather up blogs from Under the Sign of Sylvia as well as Ellen and Jim have a Blog, two.

The fourth season:

A sombre season

1 & 2: Defense of Grieving

3 & 4: House Party

5: Mr Bates no Hamlet

6: Uptick

7: Strangely Moving

8: On a green sward, in a darkened room

Coda: The Advantage of Kindness; the Kraken of Rage

Hats: Cloches and Tiaras, Season 4

Retrospective:

Mr Bates as dark hero, alter ego for Fellowes

Bates and Thomas as outsiders

From Under the Sign of Sylvia, Two:

A dream — much bewidowed Downton Abbey in need of a pussycat

Respite through Downton Abbey

Sunday: Downton Abbey in the NYC Subway & Pedro Pieti’s Underground Poetry

I’ve done most of my blogging on Downton Abbey on Ellen and Jim have a Blog, Two, but thought I’d transfer over here for this year’s list because I want to end this season with a few thoughts on the centrality of bonding with characters in this mini-series, and some characteristics it manifests and shares with most of movies in the Austen film canon — which transform them into catalyzers for cult memories. It’s not coincidence that the audience for Austen films is coterminous with that of Downton Abbey.

In his Travels in Hypereality witing of Casablanca, Umberto Eco offers a persuasive explanation for why some movies — or groups of movies, and their source too, become cult objects. He agrees with the folklorist of film, Propp, motifs and characters these are attached to, the narrative function of these are crucial — we bond with a presence whose underlying archetype, stereotype appeals personally and deeply. Fellowes offers us a cornucopia — as does Austen — of heroines.

As I admitted in talking of the lacunae of Breaking Bad for me, the core heroine is Anna. It’s she I care intensely about — and Fellowes has said he assumes she is centrally liked. I don’t like her political stance, but she is closest to my experience. How I see my place in that world — if I were lucky. It’s her story I am following, and I am drawn to her charitable character, liking for order, security, and peace; I see why she clings to Mr Bates who means to shelter and love her utterly. Anna doesn’t expect anything; she just hopes things will go okay but knows often they do not. A key to this identification is her low expectations as well as Bates’s.

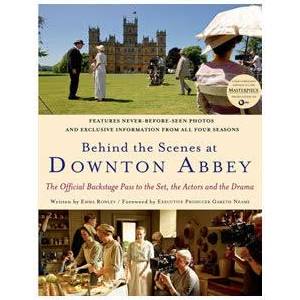

But this figure or these figures in the carpet do not leave their gratification without that carpet, which must display certain magical features. Some of these are that we should be able to break, dislocate, unhinge a totally realized world. Austen wrote and rewrote her books, so they carry many layers and fruitful opportunities for de-construction. Fellowes’s screenplays are unlike what the handbooks tell you screenplays should be like: they don’t go anywhere, much less rapidly but are imbricated, and the large vision realized auditorily and visually through them seen in the companion books, with their exquisite detail, insider information and insight (“behind the scenes”), multi-generic assemblage of elements and documents from the history of the film. Downton Abbey is also thick with stereotyped images, frames derived from the traditions of costume drama. Intertexual collage Eco calls it.

So when we approach this work we can (as Eco says) “quote characters and episodes” as if they were aspects of our world, enjoy a riot of images: say the people at the railway station, the dinner party, the male fight to the death (if only the other characters would let them), holding hands. The snatched epitomizing line of dialogue. These movies create themselves and speak to one another. I noticed yesterday in Death Comes to the Pemberley Mrs Reynolds’s, Elizabeth’s housekeeper at Pemberley, finds a place for Louisa Bidwell’s illegitimate daughter at her sister’s boarding school in Highbury (we are to think, Ah! Mrs Goddard). When Lady Glencora announces she is pregnant in the Palliser series, Plantagenet is so excited he cites a number of doctors they must visit, including of course Dr Thorne (from Barsetshire books). Evelyn Napier is easily brought back from Season 1 to be important in Season 4. And since we have bonded with these images, it is a difficult business 5 or 25 years later hiring a replacement actor or actress; shall you chose some like, someone utterly different, a compromise? (that is the hurdle the makers of a new Poldark are trying to overcome).

It really did hurt the Downton Abbey world when Dan Stevens insisted on leaving at the close of the third season.

And what the scripts and direction of these movies invariably show is an inner life that comes straight from the experience of the central film-makers and some of the principle actors and actresses. Fellowes’s notes to his scripts show how aware he is of this; Andrew Davies openly discusses his pouring of aspects of himself into his material.

It’s important for our era that the Abbey and Austen worlds present community as a strong value and ethics of compassion even if qualified by the class system outlook, but it’s not necessary.

This is my accounting for the continued success of Downton Abbey; it is central to the way I am studying the Austen film canon — as well as Andrew Davies’s or Sandy Welch’s films (to name two of my favorite film-writers).

Ellen

I have not been emphasizing the debt to Trollope in this season but it is there and strongly. Maybe another blog — Trollope lives — one way one can respond to those who say no one reads or studies him, is point to Fellowes and the sociological event Downton Abbey has become:

How many 19th c authors/tv adaptations was Down A stolen from, oh let us count the ways…….

Not that many. What Fellowes and Co. did was repeat the motifs from many costume dramas and some of the obvious techniques of the mini-series (or soap opera). The main literary sources he outlines in his first book — they include contemporary matter; that is when the show is pre-WW1 he is using pre WW1 materials, not at all necessarily high-brow: the Bates story comes from a newspaper story he followed. The costumes of the era are centrally important — research into that. Ellen