From the East Central region, American Society of 18th century Studies site: Art and Rarity Cabinet c. 1630 by Hans III Jordaens

Cassandra’s portrait drawing of Jane Austen graces the JASNA home page

Dear friends and readers,

Since 2000 I have gone almost every year to the East Central (regional ASECS) meeting, and I have gone to a number of the JASNA meetings. In view of the covid pandemic (now having killed 223,000 people in the US, with the number rising frighteningly daily), this year EC/ASECS decided to postpone their plan to meet in the Winterthur museum to next year and instead do an abbreviated version of what they do yearly.

By contrast, the JASNA Cleveland group did everything they could to replicate everything that usually goes on at at JASNA, only virtually, through zooms, videos, websites. It was an ambitious effort, marred (unfortunately) because (why I don’t know) much didn’t go quite right (to get to somewhere you had to take other options). It was “rolled out” something like the usual JASNA, a part at a time, so you could not plan ahead or compare easily or beforehand; but now is onsite, all at once, everything (at long last) working perfectly. I visited (or attended or whatever you want to call these experiences) two nights ago and last night, and can testify that since I usually myself go to listen to the papers at the sessions or lectures, I probably enjoyed the JASNA more than I usually do at the usual conference. If you didn’t care for what you were seeing or hearing for whatever reason, it was very easy to click away; you could see what was available all at once, watch far more than one intended to be given at the same time. You can skim along using your cursor …

IN this blog I offer a brief review of both conferences.

*******************************************

A detail from one of Canaletto’s paintings from around the Bacino Di San Marco, Venice: a lady and gentleman

In our “Brief Intermission,” for EC/ASECS, on Friday, in the evening we had our aural/oral experience, a couple of hours together where we read 18th century poetry and occasionally act out an abbreviated version of a play; during the later afternoon we had one panel of papers, this one about researching unusual subjects itself. Saturday morning, there was one panel of papers by graduate students competing for the Molin prize (given out for excellence to a paper by a graduate student each year); than at 1 pm there was the business meeting (sans lunch unless you were eating from wherever you were while you attended the zoom), and the Presidential Address: this year a splendid one, appropriate to the time, John Heins describing the creation, history and grounds of Dessau-Worlitz Park (Garden Realm) in Eastern Germany, a World Heritage site, with the theme of trying to experience a place fully although you are not literally there by its images, conjuring up in one’s mind, the place we might like to be but are not in. I didn’t count but my impression was we had anywhere from 25 (the aural/oral fun) to 37/40 people for the four sessions. I enjoyed all of it, as much (as other people said) to be back with friends, see familiar faces, talk as friends (chat before and after papers).

I will single out only a couple of papers from Friday’s panel. First, Jeremy Chow’s paper, “Snaking the Gothic” was in part about the way animals are portrayed in 18th century culture, focusing on snakes. It seems the identification as poisonous (fearful) led to their being frequently used erotically. I found this interesting because of an incident in one of the episodes of the fifth Season of Outlander where a bit from a poisonous snake threatens to make an amputation of Jamie’s lower leg necessary but a combination of 20th century knowhow, and 18th century customs, like cutting the snake’s head off, extracting the venom and using it as an antidote becomes part of the way his leg is saved. In other words, it is used medically. Ronald McColl, a special collections librarian, spoke on William Darlington, American physician, botanist and politician whose life was very interesting (but about whom it is difficult to find information).

People read from or recited a variety of texts in the evening; I read aloud one of my favorite poems by Anne Finch, The Goute and the Spider (which I’ve put on this blog in another posting). I love her closing lines of comforting conversation to her suffering husband.

For You, my Dear, whom late that pain did seize

Not rich enough to sooth the bad disease

By large expenses to engage his stay

Nor yett so poor to fright the Gout away:

May you but some unfrequent Visits find

To prove you patient, your Ardelia kind,

Who by a tender and officious care

Will ease that Grief or her proportion bear,

Since Heaven does in the Nuptial state admitt

Such cares but new endeaments ot begett,

And to allay the hard fatigues of life

Gave the first Maid a Husband, Him a Wife.

People read from novels too. This session everyone was relatively relaxed, and there was lots of chat and even self-reflexive talk about the zoom experience.

The high point and joy of the time to me was John Heins’ paper on Worlitz park: he had so many beautiful images take of this quintessentially Enlightenment picturesque park (where he and his wife had been it seems several times), as he told its history, the people involved in landscaping it, how it was intended to function inside the small state, and the houses and places the different regions and buildings in the park are based on. He ended on his own house built in 1947, called Colonial style, in an area of Washington, DC, from which he was regaling us. He brought home to me how much of my deep enjoyment of costume drama and BBC documentaries is how both genres immerse the viewer in landscapes, imagined as from the past, or really extant around the world (Mary Beard’s for example). He seemed to talk for a long time, but it could not have been too long for me.

Amalia’s Grotto in the gardens of Wörlitz

***************************************

Andrew Davies’s 2019 Sanditon: our heroine, Charlotte (Rose Williams) and hero, Sidney Parker (Theo James) walking on the beach …

I found three papers from the Breakout sessions, one talk from “Inside Jane Austen’s World,”, and one interview from the Special Events of special interest to me. (Gentle reader if you want to reach these pages, you must have registered and paid some $89 or so by about a week before the AGM was put online; now go to the general page, type in a user name and password [that takes setting up an account on the JASNA home page]). The first paper or talk I found common sensical and accurate (as well as insightful) was by Linda Troost and Sayre Greenfield, on Andrew Davies’s Sanditon. They repeated Janet Todd’s thesis in a paper I heard a few months ago: that Austen’s Sanditon shows strong influence by Northanger Abbey, which Austen had been revising just the year before. Young girl leaves loving family, goes to spa, has adventures &c. They offered a thorough description of how Davies “filled in the gaps” left by what Austen both wrote and implied about how she intended to work her draft up into a comic novel. They presented the material as an effective realization and updating of Austen’s 12 chapter draft, ironically appropriately interrupted and fragmentary. I will provide full notes from their paper in my comments on my second blog-essay on this adaptation.

The second was Douglas Murray’s “The Female Rambler Novel & Austen’s Juvenilia, concluding with a comment on Pride & Prejudice. He did not persuade me Austen’s burlesque Love and Freindship was like the genuinely rambling (picaresque) novels he discussed, but the characteristics of these as he outlined them, and his descriptions of several of them (e.g., The History of Charlotte Summer, The History of Sophia Shakespeare – he had 35 titles), & James Dickie’s study of cruelty and laughter in 18th century fiction (Doug discussed this book too, with reference to Austen), were full of interesting details made sense of. Of course Austen’s heroine, Elizabeth, as we all remember, goes rambling with her aunt and uncle in Derbyshire and lands at Pemberley just as Darcy is returning to it.

There have been some attempts at good illustration for Catherine, or the Bower

Elaine Bander’s paper, “Reason and Romanticism, or Revolution: Jane Austen rewrites Charlotte Smith in Catherine, or The Bower” interested me because of my studies and work (papers, an edition of Ethelinde, or The Recluse of the Lake, many blogs) on Charlotte Smith. She did not persuade me that Austen seriously had in mind Smith for the parts of her story (was “re-composing” Smith’s novels). But hers is the first thorough accounting for this first and unfinished realistic courtship novel by Austen I’ve come across, and on this fragment’s relationship to an 18th century didactic work by Hannah More, to other of Austen’s novels (especially the idea of a bower as a sanctuary, a “nest of comforts”, character types, Edward Stanley a Wickham-Frank Churchill). I draw the line on the way Elaine found the aunt simply a well-meaning dominating presence: Mrs Perceval is one in a long line of cruel-tongued repressive bullying harridans found across Austen’s work. Austen is often made wholesome by commentators — I find her disquieting. Elaine suggested that Juliet McMaster (who gave a plenary lecture, and told an autobiographical story for the opening framing of the conference) in a previous Persuasions suggested a persuasive ending for the uncompleted book. Her talk was also insightful and accurate in her description of Smith’s novels, their mood, their revolutionary outlook and love of the wild natural world: “packed with romance and revolution, bitterly attacking the ancien regime, injustice, describing famous and momentous world events, including wars — quite different from Austen (I’d say) even if in this book Austen does homage to all Smith’s novels.

As to “Special Events,” I listened briefly to an interview of Joanna Trollope and her daughter, Louise Ansdell (someone high on a board at Chawton House – why am I not surprised?): Trollope, I thought, told the truth when she said young adult readers today, let’s say having reached young adulthood by 2000 find Jane Austen’s prose very hard to read. What I liked about these comments was they suggest why it is so easy to make movies today that are utter travesties of Austen’s novels (the recent Emma) where say 30 years ago movie-makers were obliged to convey something of the real mood, themes, and major turning points of Austen’s novels.

“Inside Jane Austen’s world included talks about cooking, what to put in your reticule (and so on). Sandy Lerner re-read a version of her paper on carriages in Austen’s time that I heard years ago (and have summarized elsewhere on this blog). Of interest to me was Mary Gaither Marshall’s discussion of her own collection of rare Austen books, including a first edition of Mansfield Park (she is a fine scholar): she told of how books were printed (laborious process), how the person who could afford them was expected to re-cover them fancily, the workings of the circulating library &c. She said her first acquisitions were two paperbacks which she bought when she was 10 year old.

***********************************

This last makes me remember how I first read Austen, which I’ve told too many times here already, but it is a fitting ending to this blog.

On Face-book I saw a question about just this, from the angle of what led someone to read Austen’s books in a “new” (or different way), without saying what was meant by these words — as in what was my “old” or previous way of reading her. I can’t answer such a question because my ways of reading Austen or eras do not divide up that way. But I like to talk of how I came to study Austen and keep a faith in the moral value of her books despite all that surrounds them today, which go a long way into producing many insistent untrue and corrupted (fundamental here is the commercialization, money- and career-making) framings.

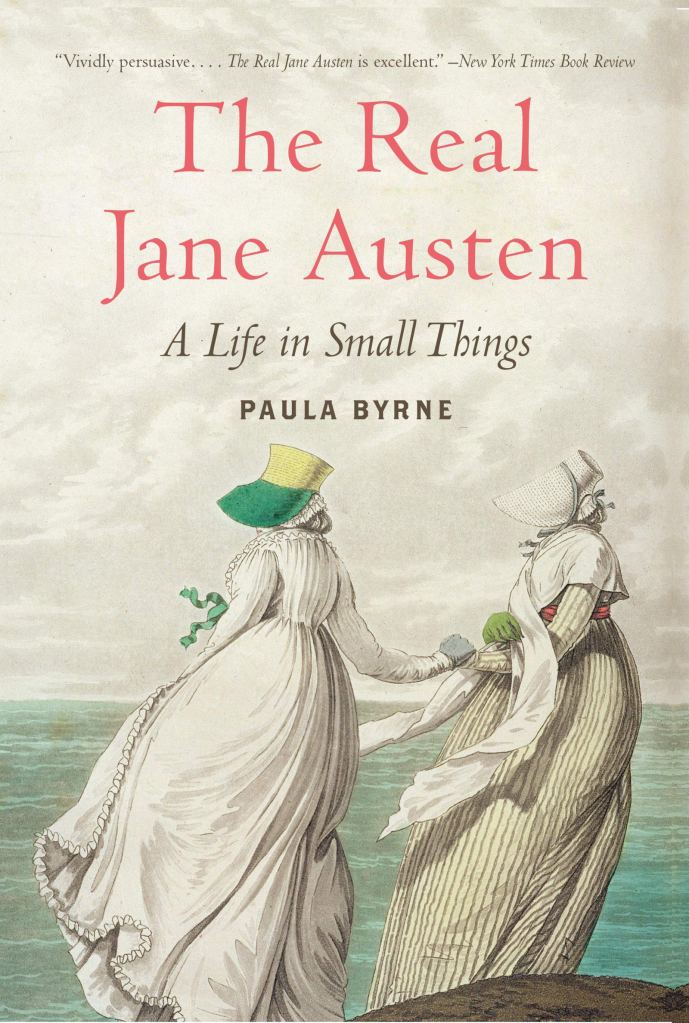

So I wrote this and share it here: Years ago I loved Elizabeth Jenkins’s biography of Jane Austen, and that led me to read Northanger Abbey and Persuasion. I must have been in my late teens, and my guess is I found the Jenkins book in the Strand bookstore. I had already read (at age 12 or so) Pride and Prejudice and Sense and Sensibility; and at age 15, Mansfield Park. Nothing inspired me to read the first two (part of this person’s question), but that the first two were there in my father’s library among the good English classics. The third I found in a neighborhood drugstore and I was led to read it because I loved S&S and P&P. MP was not among my father’s classic libraries The first good critical book I remember is Mary Lascelles on the art of the books, then Tave’s Some Words of Jane Austen. So as to “new way of reading her” (intelligently), when Jim and I were in our thirties at a sale in a Northern Virginia library Jim bought a printing of the whole run of Scrutiny and I came across the seminal articles by DWHarding (a revelation) and QRLeavis. I do not remember when I found and read Murdock’s Irony as Defense and Discovery, but it was the first book to alert me to the problem of hagiography and downright lying (though Woolf very early on gently at that (“mendaciou”) about the Hill book on Austen’s houses and friends).

When I came online (1990s and I was in my forties) of course I was able to find many books, but the one that stands out attached to Austen-l, is Ivor Morris’s Considering Mr Collins, brilliant sceptical reading. There are still many authors worth reading: John Wiltshire comes to mind, on Austen-l we read together a row of good critical scholarly books on Austen. Today of course you can say anything you want about Austen and it may get published.

I saw the movies only years after I had begun reading, and the first I saw was the 1979 Fay Weldon P&P, liked it well enough but it didn’t make much of an impression on me. The 1996 Sense and Sensibility (Ang Lee/Emma Thompson) was the first of several movies to change my outlook somewhat on Jane Austen’s novels, in this case her S&S.

Since Jane Austen has been with me much of my life, of course I welcomed a chance to experience some of the best of what a typical JASNA has to offer, since nowadays I & my daughter are regularly excluded from these conferences. After all those who have special “ins” of all sorts, I am put on the bottom of the list for what room is left. I regret to say she has quit the society because she loves to read Austen, is a fan-fiction writer of Austen sequels, enjoyed the more popular activities, especially the dance workshop and the Saturday evening ball. She is autistic and rarely gets to have social experiences. She had bought herself an 18th century dress and I got her a lovely hat. They are put away now.

When was I first aware there was an 18th century? when I watched the 1940s movie, Kitty, with Paulette Goddard — you might not believe me, but even then, at the age of 14-15 I went to the library to find the script-play and I did, and brought it home and read it. I fell in love with the century as a set of texts to study when I first read Dryden, Pope, and the descriptive poetry of the era — just the sort of writing that describes places like Worlitz Park.

Ellen