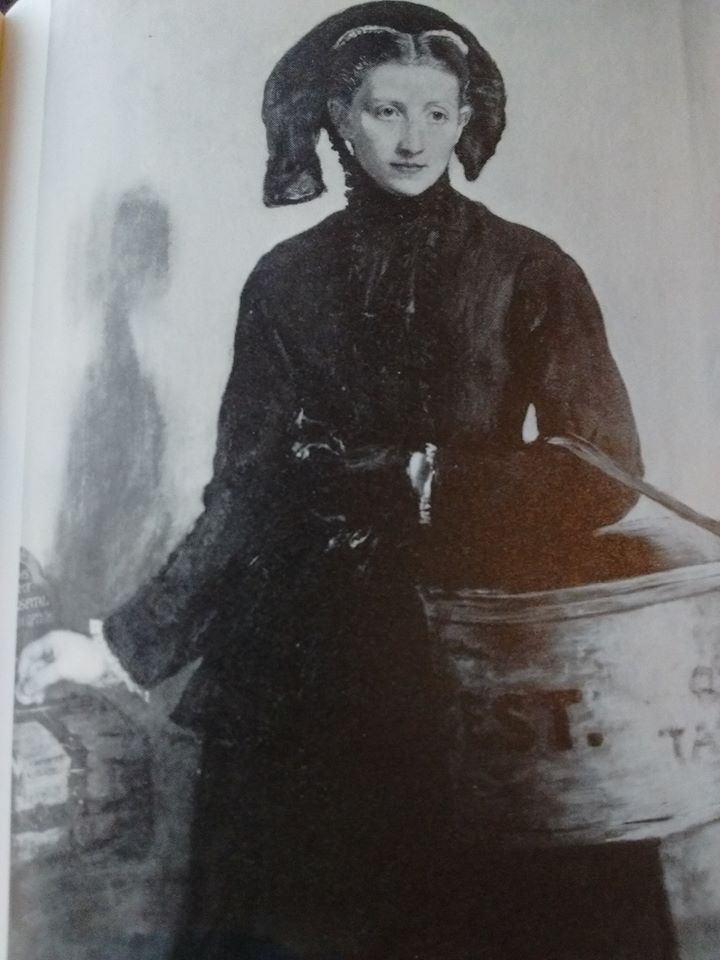

John Everett Millias, from Irish Melodies: “An Excluded Woman” — the illustration was not for Agnes, but it fits central aspects of her existence, an outlier, outsider, excluded by belonging nowhere

Dear friends and readers,

I’ve just finished reading another of Margaret Oliphant’s neglected masterpieces exploring aspects of women’s lives; I’ve written about these as a group (Novels of Women’s Lives: Marriage and Career) and individually (The Marriage of Elinor: scroll down); tonight I want to bring into play one aspect important to many of them, the widowed heroine. One reason Agnes has been neglected is that its emotional power, psychological brilliance, and just startling accuracy about the way a grieving widow might feel only begins after the first quarter of the second of two volumes. That is, Oliphant does not reach her electrifying content until she’s somewhat more than half-way through. And it does not come to the abyss of despair until her oldest child, an 8 year old boy, is kidnapped by her powerful aristocrat relatives in its concluding chapters.

Why does she take all this time? because the extremis anguish Agnes Trevelyan (nee Stanfield) knows occurs as a cumulative effect of years of life. First her suitor, Roger Trevelyan, after meeting her must contend with his family’s angry objections and threats to disinherit him insofar as they can, and William Stanfield, her blacksmith (as he’s endlessly described) father’s worry that the marriage is not a good idea for Agnes. Only William Stanfield, her noble-hearted kind insightful father (whom most of the genteel characters look down on because he is a blacksmith) finally consents generously to this marriage.

**************************

John Everett Millais — Frontispiece for Trollope’s Rachel Ray (it seems to me appropriate for Oliphant’s first conception of Agnes when we first meet her)

Upon marriage (we are past half the first volume) Agnes begins to grow up: she finds Roger may be above her in rank but he is inadequate as man and a spouse. In Italy at first Roger wants to keep her ostracized, wrongly fearing others will look down on her; she had been framed as a vulgar, low-coarse ambitious woman, stigmatized by the envious of her own class. The couple go to Italy, seemingly for a honeymoon, but eventually (it emerges) as part of Roger’s plan to avoid the consequences of his decision: work for a living, make an genuine effort to integrate his wife into his society, something she is capable of because she in nature, fine, intelligent, and has been educated by her father (mostly through reading).

The result is 7 to 8 years of isolation, with a few true friends for her and him (better types here and there) until illness, which turns out to be fatal drives Roger back to England and his and Agnes’s family, their community, Windholm.

We must also experience more fully what a disillusionment Agnes goes through with his young man; she learns his is a petty, selfish, snobbish, idle nature; one of his few admirable traits is that gradually he learns to appreciate her through their years of “living on nothing at all:” borrowing, cadging, his father-in-law sending lump sums (whom Roger verbally abuses anyway), some gambling. Oliphant shows us what it is like to live on nothing a year, abysmal, humiliating. Roger sees Agnes’s fine nature but also experiences her as a boring burden (his is a corrosive wittiness), who has also laden him with three children. She contributes nothing to the household as he sees this. When they return to England, they find that her father had built a beautiful house for them when he still expected his son-in-law to make a good living; they move in, and somehow William Stanfield keeps them afloat.

Agnes has known much emotional pain from time, circumstance, her situation and chance: she once had a close loving relationship with her father, and these years have estranged them not because they are angry at one another, but because they are unwilling to be disloyal to her husband, to face up to the realities of their lives. These include her father having remarried a deeply amoral stupid woman, jealous and envious, resentful of anyone who seems to have more than she, someone (we gradually learn) who has lived by semi-prostitution and had two sons born illegitimately from Roger’s own contemptible baronet of a father, Sir Roger Trevelyan.

This is yet another book by Oliphant which has the obsessively recurring male worthless in terms of any work he does, often drunk, often lying, irresponsible; not only does he waste money but he is sexually promiscuous and he lives in a predatory manner — off others. Give him any power and he inflicts himself and misery on others. I suspect this composite figure is her younger brother who she eventually paid in effect to stay away, with aspects of her husband, older brother and specific other men she’s seen or known thrown in.

She also has a cold spiteful sister-in-law, Beatrice, who is presented as also envious, and resentful because she is unmarried, has to live with Sir Roger, somehow (like Lily in Wharton’s House of Mirth) cannot get herself to marry a rich young man simply for his money. Agnes is innocent of malign feelings and has no idea how dangerous Beatrice could be to her or her children. After Agnes’s husband dies, and this sister-in-law and the father-in-law attempt to wrest custody of her beloved boy, Walter, from her, she does know. The court case goes nowhere because Roger did not leave a will specifying his son should be returned to his family for schooling, and because the judge interviews and discovers Agnes to be a valuable mother. Sometime after this Beatrice concocts a plan to kidnap Walter through Stanfield’s wife’s illegitimate children (her nephews though the book never uses this term of them).

Oliphant is not wholly unsympathetic to Beatrice Trevelyan: in her the condition of a spinster dependent on a cold indifferent father who will not give her much money is explored. It is only when Beatrice is discovered to have worked to kidnap Agnes’s son, that the book sees her narrowly as simply poisonous. In fact the portrait of Beatrice at different points of her life across the book is complex.

In this later part of the novel, the kindly noble male, brotherly, who loves the heroine selflessly for years, and turns up in other novels is her as Roger’s old friend: Jack Charleton understands how to navigate the court system, and custody of her child is not taken from her. As with the other male figures of this type in other novels (The Marriage of Elinor has such a male), our heroine does not appreciate Jack. She does yearn for affection from him, and is gradually turning to him, capable given time of becoming his wife, but not once she loses her boy. Agnes blames herself for the kidnapping of the boy because she was writing to a (in effect) love letter from Jack so did not miss her son at first.

There are a few women Agnes meets her or knows who are decent people — serious, truthful, capable of love and concern for others, but the novel’s third central worthy character whose presence is part of the core value to Agnes of her life is her son, Walter. His abduction leads to the tragic final chapters of the book. Her beloved son dies trying to escape from his captors – he jumps out a window and crushes his body.

******************************

John Everett Millais, said to be a print for Trollope’s “A Widow’s Mite” (where however there is not literal widow; the short story is an exploration of this parable)

So to the hidden life in this book as in others (Hester comes to mind) by Oliphant disclosed to us: long passages about widowhood as experienced by Agnes once Roger dies, shorter but heart-breakingly intense once her son dies. On widowhood Oliphant produces the most accurate truthful kinds of utterances, more central than those I’ve ever read — the closest about widowhood is Julian Barnes in the last third of his Levels of Life; the closest about how a mother can die before her body physically dies, just be there breathing on, doing what you are expected for others is in the last pages of Elsa Morant’s Storia, where after her 7 year old son dies of an epileptic fit, brought on by the school authorites, and the murder of his dog (the police) Iduzza is said to live on for 9 years, but only in her body. So too Agnes.

It’s hard to find a single passage (Matthew Arnold-like) as revealing touchstone, for like many fine novels, the language’s force also depends on cumulative effect. Agnes is not in fact literally alone: she has an 8 year old boy, two babies, one an neonate, the other not yet toddling, her father lives in a house within walking distance, and yet she has this experience of “utter loneliness which the most solitary of human beings could not have surpassed … ” Yet her desolation is unbroken, and among the phrases saying why I pick this:

there was nobody to share the burden that was heaviest. Henceforward that closest bond was rent for ever and ever. Nobody in the world could say ‘It is my sorrow as well as yours.’ She had to take it all upon her, by herself and cover it up and keep it from injuring or wearying the others, who had so little to do with it. This was also a thing quite natural, and of which no one had any right to complain.

Oliphant has just before built up to “the only real hardships in existence are those that come by nature — the only ones that are inevitable an incurable, and form which there are no means of escape.” Of course this was Oliphant’s case, surrounded by people — dependent on her once her artist-husband died, leaving her nothing but large debts and three children.

We move through the burial, the funeral and just after and with Agnes discover that she cannot go back and pick up with others what was before her marriage. Like her father, her marriage has altered her and him: Changed circumstances, long absence, and “what was still more important, the character of wife, had made between Agnes and her father a separation which had nothing to do with external obstacles.” She cannot confide in him any longer nor he her.

Oliphant describes the difference of a child’s grief for the loss of the father and hers, the child’s quickly exhausts itself, nothing left after a bit and Agnes “had already gone beyond his reach without knowing it …” — that’s also true if you turn to an animal for companionship beyond a certain point.

Then when Walter is kidnapped, she shows the helplessness of the child against adults determined to bully that child into doing what the adult wants. It is frightening and should be read by all people who vote for leaders who separate families and put children in prison.

From the final two pages of Agnes:

The vicarious life in which most women spend the latter part of their day might still remain for her; but her own life was over and done and she was not one of those who live till they die. So that I have told you all her story, as well as if I had put a gravestone over her and written the last date on it, which may not be ascertained for many years … grant to [women who have no other heritage] at the end of their many days a sweet life by proxy to heal their bitter wounds.

Agnes does have her two daughters, and her father.

*************************************

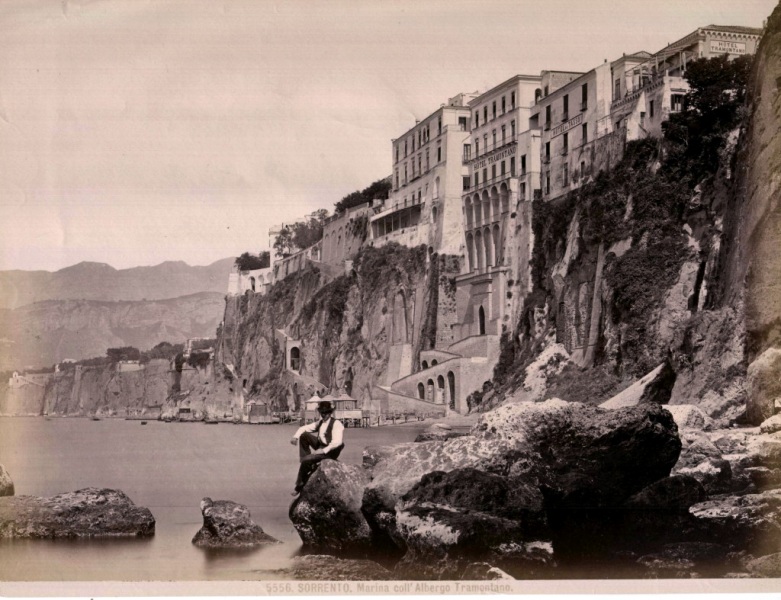

A 19th century engraving, Sorrento

Oliphant knew she was describing complex feelings and realities most novelists of her time eschewed. So she provides a preface in the Tauchnitz editin (Leipzig, 1865) where she warns the reader her book will cover material most novels never get to. She says “the great value of fiction lies in its power of delineating life” and to do this she must depict what happens in the later chapters of our existences. Novels teach us by revealing “sentiments which may be in many minds, but which none would care in their own person to give expression to.”

At any earlier point, before the boy dies, Oliphant felt Agnes needed work; she is at a disadvantage because her father support her — not having to work for a living in effect. Oliphant knows that her writing was what her life became – and had been before too, but differently. The same person living a different life.

I should remark on the beautiful evocative descriptions of Italy, Sorrento, Naples, Florence — it’s clear that Oliphant herself responded on a deep level to the landscape, cultural life, and art of Italy. It’s clear from her life that Oliphant herself loved to travel: she enjoyed research books on Italy and France because she could go there.

Oliphant declares firmly that Agnes’s experience was “no tragic exceptional case … she had only the common lot, darkened by great sorrows, but not without consolation.” This is one of many places in her writing where Oliphant questions God, and puts before us the difficulty of believing there is a good God, for who, she asks, could “be cruel enough to deprive a mother of her child,” and here “God, who was supposed to be love, had done it.” (Only the more recent scholarly literary criticism of Oliphant broaches this topic with candor).

Ellen