Friends and readers,

For my first of my new series of women artists I’m going to disagree with the some of the implications of the biography by Laura Auricchio, which book suggests a life and work where our heroine breaks through taboos, wins unusual recognition, fulfills her gifts, all while leading an independent life. She did indeed lead a courageous independent life if by that we mean she left a mistaken marriage quickly, was well-educated, trained in the best schools a young woman might find in France, and apparently lived as a single professional woman supporting herself and others for many years– in the face of all sorts of obstacles from ridicule to threatened possible imprisonment. The qualification is the result of her life-long relationship with her teacher and mentor, then friend and promoter, and finally lover Francois-Andre Vincent (his teacher had been Joseph Marie-Vien [1716-1809].) Following the records of her we find her continually doing what she had to do to get herself and her work accepted into what academies she could, obtain and paint paying clients (some of them remarkable people), and have her work exhibited in the right places. We find good and useful friendships (with other women, with clients). She survived the revolution, no mean feat, herself painting a series of National Assembly deputies, painting on into the last years of her life.

On a humane intimate level, it seems that one of the two famous pupils in her best known (beautiful) painting, of herself with two pupils, namely Marie-Gabrielle Capet (1761-1818) was Vincent’s daughter and became for Labille-Guiard a beloved (step)-daughter:

The other girl is Carreuax de Rosemond (d. 1788)

Marie-Gabrielle was lovingly painted a number of times (close-ups), e.g.,

Study of a Seated Woman Seen from Behind (Marie-Gabrielle Capet), 1789

She lived with Labille-Guiard and Vincent for many years; well past her (step-)mother’s death, she named Vincent as her father (and was his primary beneficiary). Late in life, Marie depicted Labille-Guiard surrounded by a group of male artists, while she paints Joseph Marie-Vien, to the side is an older Marie herself. She had become a painter in her own right calling herself Gabrielle Capet. A close-knit family of three artists. Adelaide’s father had been a successful marchand du corps de la mercerie, his shop was in an area of Paris which was a center for theater, music and dance, their street near the Louvre where the Royal Academy had its headquarters, with favored painters and sculptors living and working nearby. Madame de Barry was at one time an employee in her father’s shop. There had been 8 children (all but she dead by 1783). Her mother died in 1768, and a year later she married a neighbor, from whom she was legally separated in 1779. She married Vincent in 1800.

Where I part company from Auricchio’s study is I take Labille-Guiard’s work as an artist to have had (to use Germaine Greer’s words) an “illusion of success” rather than the real thing. Why? She paints as effectively and ably, with psychological astuteness Elisabeth Vigee-LeBrun rarely achieves, in the earlier part of her career as she does the later. With a genius level talent for depicting aliveness, skin, textures, nervous brush strokes, moods, she never develops into anything else but a portraitist, and these remain oddly still. However later in her career she is forced to tone down the luxurious and rank- and reward-based accoutrements, extravagant costumes, furniture she seems to have delighted in painting, so that the portrait concentrates more than ever on the person’s face and body, yet she is essentially making the same kinds of portraits over and over. She flatters her clientele, has them lavishly enact admired norms (in the case of women breast-feeding, with children hanging all around them, or presented as deeply sensual), follows whatever she thinks will be approved of, and remains decorous (sometimes in the face of ridicule, implicit or open dismissal). When it’s not a case of elite requirements, she is hemmed in by new revolutionary codes. Late in life she shows her group hierarchical scenes are done out of more than commercial and respectable considerations, for she produces the same kinds of worshipful ancien regime type group hierarchical scenes she began with. Like Orwell’s horse at the end of Animal Farm, she cannot resist a ribbon, and elevates Madame de Genlis late in life with a satin and lace gown, “a spectacular headpiece of ribbon and lace” and (to me) unsettling green leather gloves:

When she rises out of the usual, ordinary, expected, it’s because something in the person him or herself comes through or Adelaide’s own love for her subject lifts the painting.

Again Marie-Gabrielle Capet, 1798, a somber portrait – the girl smiles hiddenly

Or some inexplicable or unexplained allegiance, as in the emotionally intense strange

Portrait of Louisa Elisabeth of France (painted 1788)

Not the least fascinating element of the above often-reprinted image from Labille-Guiard’s portrait of the (once) Duchess of Parma with her two year old son, is that the Duchess died in 1759; Labille-Guiard was 10 at the time, so this is a probably a completely faked picture. Art criticism can go on and one about the combination of sentimental romanticism, hierarchical rococo neo-classicism, mothering in a fantastical hat whose feathers are repeated by the parrot on the one side, and white curtain to procure a shadow on the other, but it is as unreal a put-together set of alluring arms, hands, bosom, dress, with a waif-like child on a oddly sunny balcony (as if a film camera were spot-lighting the area) as you are likely to come across.

Auricchio’s study keeps to a sensible track. It may be read as a history of what helped but far more often stifled and got in Labille-Guiard’s way. In her early years of training (which included pastels), she studied with respected minor and well-known painters, one of whom, Alexander Roslin (1718-1793) was especially supportive of female artists, and nominated Adelaide for membership in the Royal Academy in 1783. In the first chapter she is attacked by the relentless comte d’Angiviller who did everything he could to exclude women from the Royal Academy and stop a commercial exhibition she was part of; at the same time she is supported by a bourgeois entrepreneur, Claude-Mammes Pahin de Champlain de la Blancherie-Newton (whew) who staged popular and varied art salons and praised her work strongly. She did learn to produce precisely the sort of work that was expected of her gender, class, even marital status. She also chose subjects which advertised, confirmed and validated her as in this or that network of support. I’ve chosen from this part of her career one which shows a favorite motif: the artist doing his or her work

Portrait of the sculptor Augustin-Pajou Modeling the bust of J.B. Lemoyne (a pastel)

Still she and other female artists were primary targets for virulent tracts presenting lewd gossip; she turned to the comtesse d’Angiviller against a gross libel that hurt a client. It’s no wonder her career stagnated. She seems never to have considered trying a landscape, a still life, anything truly expressionistic (like Angelica Kauffman). When she was strongly praised, she tried to use the moment to ask for lodgings in the Louvre, which she was not granted (but given a pension of 1000 lives instead). She also ran a school for other female artists. Dena Goodman has studied her work from this period and finds the way Labille-Guiard presents her women in what is clearly a public space (meant for men then) gives them gravitas and a place in the world.

Come the revolution, new fights and struggles (though over similar things) occur where she took a pro-active role for women and moderate reform; at one point she is mocked mercilessly. Transition was tough as fleeing aristocrats don’t remember to pay their bills, new patrons are needed, her worshipful style towards aristocrats not changing, she finds her one entry poorly received. Unexpectedly, she painted Robespierre, about which we are not told very much; discouragingly, this is another of her paintings to have gone missing. At this point she casts her lot (or informally joins) a group of political moderates; most of her paintings of this era remain untraced. Iconoclastic fervor destroyed one of her works. She retreats, retrenches, leads a quieter life; together with friends and family members she buys property, tries legally to secure income to Vincent’s daughter and another young woman and even continues to try to obtain lodgings in the Louvre.

Her work changes again, becomes smaller, less idealized, more somber. Now no women were allowed in the Royal Academy, yet we find her re-grouping and painting again. Two works from this later post-Revolutionary period:

Portrait of Joachim Lebreton — she is still keeping away from us the inner life of the more simply dressed and framed man — he was the head of the museum department of the Committee on Public Instruction, a leading art institution

Portrait of the Comedian Tournelle, called Dublin, 1799 — he had been imprisoned for performing Richardson’s Pamela (deemed controversial and unpatriotic)

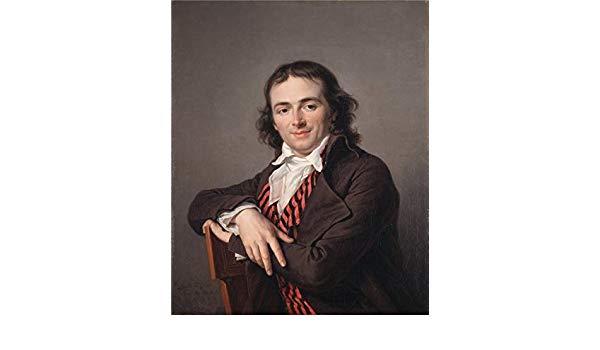

I’ll end on an earlier work (for as I suggest the earlier works can be as good and interesting as her later), executed perhaps around the time she painted herself (1780), a portrait of her partner and husband, Francois Andre Vincent

Considered the leader of the neoclassical movement until he was usurped by Jacques-Louis David … [his wife paints Vincent] fully within neoclassicism … this painting is interesting for its wide range of colors, achieved with very little tonal variation … Labille-Guiard displays superb technical dexterity in color and tone which allowed her to perfectly integrate the foreground with the middle and backgrounds and the outlines of the figure with the surrounding space. The interplay between the lateral illumination of the face, the darkness of the other side of the face, and the light in the background contributed to an atmospheric school that would extend throughout Europe (Jordi Vigue, Great Women Masters of Art).

You could say she was a stubborn portraitist. She does not appear to have owned a cat nor painted any pet-companions. One begins to find this in this era. Her life-span id closely similar to that of Charlotte Smith.

Ellen

Three main sources:

Laura Auricchio, Adelaide Labille-Guiard: Artist in the Age of Revolution. LA: Paul Getty, 2009

Germaine Greer. Obstacle Race. NY: Farrar, Strauss, Giroux, 1979.

Jordi Vigue. Great Women Masters of Art. NY: Watson-Guptil, 2002.

See also:

Emma Barker, ‘Women artists and the French Academy: Vigée-Lebrun in the 1780s’, in Gender and Art, ed. Gill Perry, Open University/Yale University Press, 1999.

and my other blog-essays on women artists of the long 18th century on this Austen reveries blog. Beyond Angelica Kauffman (linked into the blog), type in their names on the search engine e.g.,

Francois DuParc:

Mary Beale:

Anne Vallayer-Coster:

I have written about early modern, 19th and 20th century women artists of all sorts too, most of the time also following my own taste.

Fran: “This, too, was much appreciated, especially as it concerns an artist I knew very little about.”

Thank you, Fran. I was in doubts about the way to do it. Earlier ones I would have supplied much more detail (many more names) and told more of specific incidents, and not really aimed for a sort of portrait of my own. I cited the biography where you can find the detail (often so dismaying — stupid attacks on her as a woman) and thus kept the blog shorter. I was bothered by the anti-revolutionary stance of the biographer and felt that got in the way of her critiquing L-G.

I hope to do the same for the actress ones I do. I told myself I would find biographies of them first. Next will be Susannah Cibber and then Catherin Clve.

And do more contemporary popular ones where I don’t know so much just “celebrate” the actress, e.g., Barbara Flynn for example.

And foremother poets in this style — probably no biography for the recent ones.

E.M.