Charlotte (Rose Williams) as she comes out into the sunshine and her first full look at

You and I, you and I, oh how happy we’ll be

When we go a-rolling in

We will duck and swim ….

Over and over, and under again

Pa is rich, Ma is rich, oh I do love to be beside the sea

I love to be beside your side, by the sea,

by the beautiful sea …

Friends and readers,

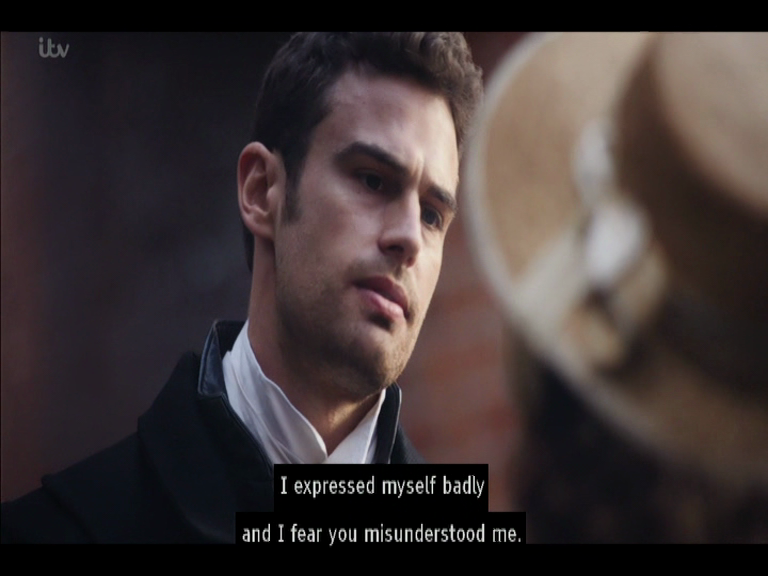

This experimental or innovative Jane Austen is not an appropriation: this is heritage all right. All the people in costume. If you attend carefully to the twelve chapter untitled fragment, the last piece of writing Austen got down (1817), known in her family as Sanditon, and then equally carefully into the continuation added by her niece Anna Austen Lefroy (probably after 1830), you will find that a remarkable number of the details and slightest hints have been transferred and elaborated from both texts (plus possibly a third, Marie Dobbs’s continuation) into this eight part series. Davies and his team (there are several writers, and several directors, though Davies is credited throughout as the creator, and has written a good deal of what we hear), the team have also availed themselves of Davies’ previous film adaptations from Austen: so the angry hardly-contained violence of Mark Strong’s Mr Knightley (1996 BBC Emma) has become the angry hard-contained violence of Theo James’s Sidney Parker:

This strident Sidney is one on whom apologies have no effect: he returns sarcasm and rejection: “I have no interest in your approval or disapproval”

The rude intrusive domineering insults of all Lady Catherine de Boughs and Davies’s Mrs Ferrars have become part of Anne Reid’s Lady Denham; the clown buffoonery of minor-major characters in Davies 2009 Sense and Sensibility just poured into Turlough Covery’s Arthur Parker &c.

And they have scoured all Austen’s texts (letters too) for precedents: female friendships and frenemys everywhere, game-playing (including cricket), piano playing where fit in, wild and heavy beat dancing, balls, show-off luncheons, water therapy — though they have nonetheless switched from the single feminocentric perspective of Charlotte of Austen’s present Sanditon (all is seen through her eyes, with the emphasis throughout on the women) to a double story where Sidney and Tom’s (Kris Marshall) two stories run in tandem with, and shape, Charlotte’s

Here Sidney and Tom are standing over Charlotte coming out from underneath the desk, discussing what they are to do next, the men call the shots, stride by seemingly purposefully — though except for Stringer they seem to have nothing much to do …

Charlotte’s story in this movie itself is continually interwoven with, shot through by, the on-going separate highly transgressive sexualized stories of 1) the incestuous Edward and Esther Denham (Jack Fox and Charlotte Spencer), 2) sexual abuse from childhood by men and now Edward and social abuse from her aunt seen literally in Clara Brereton’s (Lily Saroksky) doings (which seem from afar to include forced fellatio or jerking Edward off), and 3) young Stringer (Leo Sluter)’s aspirations in conflict with his loyalty to his entrenched-in-the-past father.

Charlotte glimpsing, shocked, Clara and Edward (in the book she sees them from afar compromised on a bench), a few minutes later the upset Clara is given no pity by her aunt

If you add in Charlotte’s pro-activity on behalf of getting Miss Georgiana Lambe (Crystal Clarke as “half-mulatto” — Austen’s phrase) out of trouble, out of her room, and unexpectedly into flirting with an appropriate African-born suitor, now freed and working for the abolition of slavery (Jyuddah Jaymes as Otis Molyneux), you have a helluva lot of lot going on.

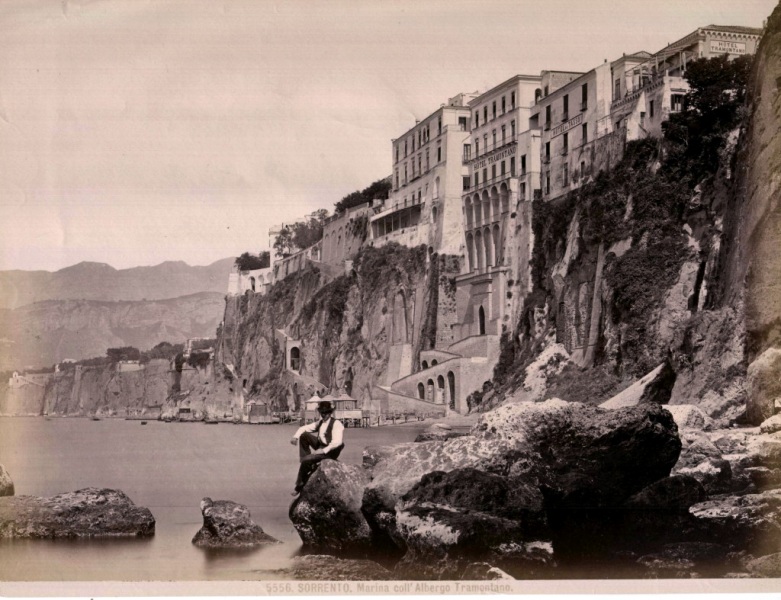

This is the busiest and most the most frolick-filled Austen adaptation I’ve seen (perhaps with the exception of the violent-action-packed Pride and Prejudice and Zombies) with an upbeat lyrical music that turns into a sharp beat rhythm now and again. Episode 1 after frolicking on the beach and in the water (twice) ends in a long gay dance-sequence. Episode 2 after more bathing (Charlotte rising from the sea), a super-luxurious dressed-up luncheon, with some excoriating wit and a rotten pineapple (talked about as an erotic object, seemingly phallic), and attempts to flee to London inside a mocking crowd, ends in several walks into the cliffs, with a apparently near suicide by Miss Lambe (rescued, just, by Charlotte), and a sexualized water clash (Sidney has tried to escape by diving in, only to discover in front of him as he emerges naked, Charlotte). Episode 3, a wild water therapy machine sequence by the latest of mountebanks or doctor-quacks, Dr Fuchs (Adrian Scarborough), followed by a serious accident inflicted on Stringer’s father, mostly the fault of Tom Parker for not paying them enough so they can have more workmen, but one which brings together Sidney and Charlotte for their first understanding (like other recent film heroines she is a born nurse) and walk on the wet beach.

Again amid the first love romance, Otis jumps off the boat to show his despair and they frolick over the splashing

And Episode 4, back again to scenes on the beach with varying couples (e.g., the genuinely amusing pair of Diana [Alexandra Roach] and Arthur, this time on donkeys), an escape to a woodland and canoeing up river (Charlotte with the uncontrollable Georgiana and compliant Otis), ending in a return to ferocious quarreling between Sidney and Charlotte after he witnesses Rose Williams’s funny parody of his own (Theo James’s) physical quirks in performance.

Rose Williams has caught the way he holds his elegant cigarette holder, his voce tones and the emphatic aristocratic (?) rocking of his body

The series does what it sets out to do: provide the pleasures of the place. The beach, the sea, the sands, the waters and landscape form another character, an alive setting. The series is fun to watch — from the bathing to (for next blog) the cricket playing. But is this series any good? you’ll ask. Yes, I think it is. Charlotte does not own the story, it’s not so centrally hers (as it feels in the book), no, but Davies has created through her a character who is a cross between the joy of life and longing for experience we see in his and Austen’s Catherine Morland (Felicity Jones), with the keen intelligence and wit of Elinor Dashwood (Hattie Morahan) and querying of Elizabeth Bennet (Jennifer Ehle) combined. Charlotte is (to me) so appealing, given wonderful perception lines and before our eyes is growing up. I feel I have a new heroine out of Austen.

And our heroine has a new friend, Georgiana, whose mother was enslaved: they go for walks together

The series also weaves the centrality of money in our lives: to be used as part of our obligations to others, our responsibilities and how they tie us to one another. While the overt sexuality will leap at most viewers, including a sadomasochistic courting of Esther by the gallant Babbington (Mark Stanley is as effective as Charlotte Spencer — she is remarkable throughout), the drum-beat theme is money, finance, as it is in Austen’s Sanditon — and also the other film adaptation to come from Austen’s book with Lefroy’s as part of the frame (Chris Brindle’s).

Tom Parker is attempting to make a fortune by developing a property he owns, but has no capital for and he is doing it off money originally earned by Sidney (it seems, ominously, in Antigua, when he may have known Miss Lambe’s late father who would be the person who left her under Sidney’s guardianship) and now secured by loans. He has built a second house, he hires men he doesn’t pay, takes advantage of securing on credit tools and materials he has not bought; at the same time he goes out and buys an expensive necklace for his wife, the “gentle, amiable” (as in Austen’s book), Mrs Mary Parker (Kate Ashfield), who complacently accepts his lies. Critics and scholars have suggested the background for this is Henry Austen’s bankruptcy and what Austen saw of finances through that (see EJClery, the Banker’s Sister).

At the close of Brindle’s play, Sidney comes forward to maneuver humane deals out of the corrupt practices of Mr Tracy (a character found in Lefroy) with Miss Lambe’s money; in contrast, at the close of Davies’s eighth episode, we see Sidney agree to marry a very wealthy woman whom he dislikes very much but has a hold on him from his past (unexplained). Lady Denham is the boss of this place because she has a fortune; her nephew and niece are at her beck and call because they hope for an inheritance. Clara is similarly subjected to her; the hatred of Esther for Clara and Clara’s fear and detestation of Esther comes from money fears. Mr Stringer dies of his accident: exhausted, he sets the room on fire when his son has gone out for some minimal enjoyment. Not land, not rank, not estates but fluid money.

What Davies shows us is Tom continually pressuring Sidney to borrow more, Sidney resisting, then giving in and coming back with money, and then Tom wanting more. As the first season ends, Sidney has had to say to Tom the banks will give him no more and he does not think he can borrow more and ever get out of the hole they are in.

Mary asking Tom if Sidney has given him hope (and money to come)

and Tom lies, handing her a necklace he has just bought which he cannot begin to afford …

I am not sure that Austen’s fragment meant to center on the power of banks. Her book’s central theme is or seems to be illness, and this is either marginalized, or erased in the film, at most (in the assertion of feebleness in Arthur and Diana) immeasurably lightened: Austen wrote the fragment while dying and probably in great pain, and she is, as she does throughout her life, exorcizing her demons through self-mockery by inventing characters with imaginary illnesses. She certain does in the fragment write about breezes, and light, and sun and the sea with longing, but it’s not the longing of joyful youth, but the ache of the older woman remembering what she has been told about the sea and air as

healing, softening, relaxing — fortifying, bracing, — seemingly just as was wanted — sometimes one, sometimes the other, If he sea breeze failed , the sea bath was certainly the corrective; — and where bathing disagreed, the sea breeze alone was evidently designed by nature for the cure (Ch 2. p 163)

Austen’s fragment also gets caught up with literary satire as she characterizes Edward as a weak-minded reader of erotic romantic poetry and novels. Perhaps as with the long travelogue-like passage of Anne Elliot staring out into the hills in Persuasion, Austen intended to cut some of this kind of detail. But with Lefroy’s continuation and (I suggest) Brindle’s extrapolations (see Mary Gaither Marshall’s paper summarized), we can see that Davies is moving towards the same resolution. Austen’s fragment is waiting for Sidney to come to Sanditon to fix things — each reference to him while suggesting his cleverness, irony, sense of humor (and of the ridiculous too) also presents him as intensely friendly, caring for his family, responsible, and as yet in good economic shape (see Drabble’s Penguin edition of Lady Susan, The Watsons, Sanditon, pp Ch 5, pp 171, 174, 176; Ch 9, p 197; Ch 12, p 210)

Young Mr Stringer and Charlotte confiding in one another

The series suggests that outside this world of genteel people is another very hard one. The various people that Diana Parker and Tom want Mrs Mary Parker to apply to Lady Denham to relieve are made real in Austen’s Sanditon; in the workmen we see, the people on the streets doing tasks, our characters on the edge of homelessness we feel the world outside — as we rarely do in most of these costume dramas. Chris Brindle’s play makes much of the specifics of these vulnerable victims of finance and industrial and agricultural capitalism in the dialogue of the second half of his play — how when banks go under everyone can go under and the banker (Mr Tracy) hope to walk away much much richer.

So the latest Jane Austen adaptation is a mix of strong adherence to Austen and radical contemporary deviation and development.

Not that there are not flaws. Sidney is made too angry; it’s one thing to clash, misunderstand, and slowly grow to appreciate, but as played by Theo James he has so much to come down from, it’s not quite believable that our bright and self-confident Charlotte still wants him. He is an unlikeable hot-tempered bully. The only explanation for her attraction to him is he is the hero and Stringer not a high enough rank, for the scenes between Stringer and Charlotte in Stringer’s house, & walking on the beach together, on the working site, are much more congenial, compatible. The writers have made too melodramatic Esther and Edward Denham’s and Clara’s story too.

On the transgressive sex (a linked issue): I see nothing gained by having Theo James expose himself to Charlotte, except that the audience is shocked. This is worse than superfluous to their relationship; it is using the penis as a fetish. The incest motif functions to blacken Edward much in a modern way similar for the 18th century reader to his admiration for the cold mean pernicious rapist Lovelace (in the book he wants to emulate the villain of Clarissa). I grant Charlotte Spencer’s lingering glances of anguish and alienation, puzzled hurt, at what she is being driven to do (accept Babbington) are memorable.

In general, the series moves into too much caricature, exaggeration – the burlesque scene of the shower is possible not probable, as when it includes Clara in her bitter distress reaching for a mode of self-harm — burning her arm against the red-hot pipes bringing in the lovely warm shower water. But it feels jagged. Too much is piled in in too short a time. Space we have, but there needed to be more money spent on continuity and development of dialogues within scenes, in both the briefer plots and the central moments between Sidney and Charlotte. I felt the quiet friendship seen between Mary Parker and Charlotte, and again Stringer and Charlotte on the beach (at the close of Episode 4) in companionable silence were some of the best moments of the series — as well as the wonderful dancing.

We are half-way through the PBS airing. I look forward to the second half. I have seen this ending and do know how it ends, and to anticipate a bit, I do like the non-ending ending. When we get there ….

An unconventional hero and heroine would have an unconventional ending … walking quietly by the sea

Ellen